|

Click here to return to the main site. Guy Farley (composer) - That Good Night British musician and composer Guy Farley was born on 05 February 1963. His work includes orchestral scores, world music, electronica and collaborations with pop artists including Tokio Myers, Emile Sande, Paloma Faith and Mica Paris. Notable scores include Mother Teresa of Calcutta (2003), Modigliani (2004), The Christmas Miracle of Jonathan Toomey (2007), Mary of Nazareth (2012), The Hot Potato (2011), and Tula: The Revolt (2013). Darren Rea chatted with him as Caldera Records released his latest soundtrack That Good Night (2018) on CD... Darren Rea: Your latest score, That Good Night, has just been released by Caldera Records.

Guy Farley: Yes and the UK film release has changed a few times moving from February, to April to the 11 May [2018]. I'm not sure which cinema chain is showing it but Stephan (Eicke) at Caldera was very keen to get the soundtrack out in time for the film release. One of the things that's difficult, particularly with independent films, is that if you write a soundtrack worthy of release the only way that people get to hear it, apart from word of mouth, is by seeing the film. And if it's an independent film that doesn't get the light of day, or has a very small cinematic release or goes straight to home media release, it will limit the number of people who will be exposed to the soundtrack. So Stephan was very keen on this occasion to make sure he'd got the release in time for the film, but of course it's ended up being earlier than the film. It's always a lovely thing when you see a film with a beautiful score and then you go out and find it and listen to it on its own. I have always enjoyed this. You're the only composer whose scores we've reviewed and every single one has received full marks. It's the fact that they all seem to work as wonderful standalone albums of music on their own that makes them so appealing. It's really difficult to get that right, because I can't go into a film thinking: "I'm going to write a beautiful soundtrack album" [laughs], because I'm not. I'm secondary. I'm not primary. My music has got to serve the film. I've lived my entire life enjoying soundtracks and film scores outside of the film. I love them in the film and I love what they do and I'm the first to admit that when music serves a film properly, and it doesn't stand up on its own, it has done what it's meant to do. I re-scored a film called Tsotsi some time ago and the producers wanted a much more lyrical, melodic, engaging score than the one it had on it. I saw the film, which was very powerful, it went on to win an Oscar, and I did re-score the film. One of the things I found so difficult was that I couldn't write the score they wanted because the film was so powerful it wouldn't take it. At the end of it, when I listened to what I'd written, it worked perfectly in the film but it didn't work on its own... What's the point in releasing a boring soundtrack? It's the same with Classical music. I hate listening to albums that don't offer a pleasurable listening experience. I reviewed a CD recently which was composed for an exhibition of an artist and while I got what the composer was trying to achieve, I just hated it. She emailed me and thanked me for my constructive criticism and revealed that she hated it too, but it was a commission and that was the brief...

I went to the Royal College of Music recently to hear a piece by Boulez [Pierre Boulez - 1925-2016] after he'd died. I was a big fan of Boulez and I really wanted to understand him more - where his musical journey had taken him in his life and his deconstruction of music and what it became for him, because it's very intellectual. I went to this performance [laughs] hoping with my ears and with the life I've lived in music that I'd be completely engaged and inspired... and I just didn't get it [laughs]. I remember thinking: "Why has he reduced music to this? Why must it be so unlistenable?" I met the wonderful composer John Adams, at a concert where they were performing his music, he sat next to me. He's seen as a minimalist writer. One of the things that I loved about John Adams is that he brought back real beauty to his writing in the minimal idiom; real beauty in music. In 'Harmonielehre' there are inflections of Rachmaninoff, Debussy and Mahler. There are moments of such exquisite beauty in that piece and I find it such a joy to find that in modern music - where the composer has really conveyed deep emotion - because most of my life the music I've listened to has been about that: about the emotional impact that it has on me. Do you think that it's all subjective though? Do you think someone can listen to a minimalist piece and be moved emotionally? I went to see Steve Reich's Different Trains performed the other day and it was absolutely outstanding. Steve Reich, Philip Glass, Michael Nyman, these are the minimalists. I've seen Michael Nyman - I've worked with Michael Nyman - I've seen him in concert, I've seen Philip Glass's operas and concerts. I thought Different Trains was brilliant. I was completely and utterly absorbed in it. It made me realise how good Steve Reich is. When I was young I couldn't listen to 'The Rite of Spring' [Stravinsky]. I didn't understand the dissonance in it and the bi tonality and the tri tonality in the music. I couldn't listen to it at all. It was horrible. Now it's one of the most important pieces to me and I find so much beauty in it. So, [laughs] yes. I think you can find beauty in all things. When you're working on a project do you prefer a director who is very clear on what they want musically and is heavily involved with the score, or one that leaves you to find the tone of the film yourself? The answer is that they both work. I remember when the director John Irvin said to me: "Would you like to hear my film with temp music or without?" No one had ever asked me that before. And I said: "John, unless you think the temp music is important, that I hear what you've put on it, then I would rather hear it without. That gives me a completely clean palette." So I'd rather do that. I often find it easier to work with a director who says: "Look, I know nothing about music. I can only say whether I like it or I don't." I can then be a composer.

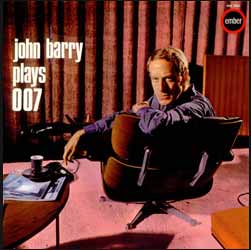

It's arguably more difficult when a director comes along and says: "Oh, we love this piece we've put on here..." and when I start playing what I've written they say: "Can you just go back and play what we put on there." What does that mean? What's the result of that, that you end up copying what someone else has done, which was written for another project? Unfortunately it's a sad thing because when composers are not allowed to compose - when they are being manipulated by references to other music and and pushed into re-writing it - there's no originality is there? The composer is not being a composer. Imagine what it would have been like going to Lalo Schifrin on Bullitt and saying: "Actually, would you mind copying this Henry Mancini score or copying this Bernard Herrmann. Just do it like he did in that film." And then imagine what it took for him to be allowed to write that music. I think that's one of the most outstanding scores of all time. This isn't meant as an insult, because I love this score of yours... but when I first heard your music for The Hot Potato, I momentarily thought I was listening to an old John Barry score or an old Mancini score I'd never heard before. Was that an instance of the director asking you to mimic their style? When I first met the director, Tim Lewiston, I said to him: "So what you're really asking for... is you want me to write a '60s score". And he said: "If I could resurrect John Barry, and get him to write the score for my film, I would. And that's what I want you to do." He said: "I'm not trying to make an original '60s movie like The Ipcress File, this is a funny tale based on a true story set in London in the '60s. What I really want to do is to capture the sound of the movies in that era, but not to take it too seriously." He pretty well gave me carte blanche just to go and write completely in that idiom. You could say the same of The Incredibles or Austin Powers for example. If someone says to me they want John Barry Bond music, I'm very happy to write it because I grew up loving that music. In The Hot Potato score you will hear all of those composers: Lalo Schifrin, lots of John Barry, Henry Mancini. It was like going back in time. It was wonderful for me to be told I could go and write in that style. It really is tongue in cheek, it's a complete nod to it and I enjoyed every second of it. I saw recently that it's available to buy now for £50 online...

I scored a film some years ago called Mother Teresa of Calcutta [2003] with Olivia Hussey in the lead role. There was some fall out between the UK producers and the Italian producers and they released a soundtrack to it which sold out. Because they couldn't agree on whatever they'd fallen out about - music rights or something - it was never released again. Someone sent me an email saying: "Have you seen how much the CDs are going for?" I think one was sold for €550! I didn't even have a copy of it. I've got the score but I don't have one of those first CDs that was released. Then there was another one. Modigliani was released by Milan, they had a fall out with the UK producers so there was only a limited release. It was then re-packaged and re-released by the producers in the UK but the Milan release, which was a run of about 500 copies, sold out quite quickly. One of those CDs went for €400 or something close. It's amazing. What are your views on online streaming sites like Spotify? Where basically people can play your music for free? Well, they do, but Spotify pay royalties to composers now based on the number of streams. This is where the industry was turned on its head, in the digital age. Nobody knew, especially all the record companies, what was going to happen and how artists were going to be paid and how they were going to earn money. I feel that it's found its way now because everything is being valued in terms of broadcast value, of which Spotify is one. So, I have received royalties from YouTube... I don't think I've ever put anything up on YouTube. I think there's about 65,000 hits, or videos under my name on there. I received the first royalty statement for the last year. It's really good to see that it's being turned into money because it's fair, or becoming more fair. With Spotify it's the same thing. I'm not putting my soundtracks up there but they are being put up by the labels and I think the figure is something like £4000 per 1 million streams. So, if it's turned into income, then it's fair. But if it's all free how is the artist supposed to survive? I've never made money out of my soundtracks, I suppose I receive MCPS [Mechanical-Copyright Protection Society] royalties but these soundtracks sell in their hundreds as opposed to tens of thousands so they don't really earn a lot of money. I put them out there for the same reason that I bought soundtracks all my life. Also I get emails every month from people saying: "Can I have this; Do you have the sheet music for that; Will you ever release this..." because everyone can contact you these days. You released a deluxe edition of Modigliani through Caldera in 2016. On the audio commentary you recorded for that score you said that once you've finished a project you don't like to go back and listen to it... I don't really. I find it difficult to go back. How did you feel revisiting this score? You rerecorded it didn't you?

I didn't re-record the score. What Stephan [Eicke] wanted me to do was to go through all the music in the film, there were many other pieces that I'd recorded for the film that weren't on the original CD soundtrack release. I do remember that we did a specific mix session for the Milan CD release but they only wanted X-minutes of music on the album, they didn't want every single piece used in the film. Stephan wanted to examine everything that was used in the film. For example there had been some Spanish guitar music written for one scene and a tango written for another scene. Stephan, as the producer, wanted to listen to everything and put together a new soundtrack. One of the things I did record was an arrangement of the Modigliani theme for piano and cello and we did go to Air Studios and record that for the Caldera album. So it was a different experience. I didn't need to go back and examine all the pieces of music again. Stephan put the whole order together and he decided what was going to go on it. I just had to make sure everything was properly mastered and that everything added up and made sense; a good listening experience. Were you forced into taking up the piano as a child? God no! Not at all. It was completely natural. I went to sleep at night hearing my mother play Chopin, Mozart and Beethoven and I think that I was fascinated that you could sit down and this instrument could produce this beautiful sound. She told me this story the other day. When I was about two years old she played me some music - I think it was Prokofiev, it may have been Peter and the Wolf - and she said I just dissolved into tears. So she played it to me again and the same thing happened again. She couldn't believe that such a young child could be so moved by music. But whatever it was she played me genuinely moved me to tears. She said: "I knew very early on that music touched you deeply." What used to happen is that from a young age I would watch her playing the piano and when she left the piano I would sit at it and play. I could make things happen. And that's really where it started. I suppose I started piano lessons at seven, when I started school. In fact, I started earlier than that, I started at pre-prep school so I was probably about the age of six, being taught by nuns who would sit there with rulers and slap your hands if you played the wrong note! I carried on until the age of 18 it was a long musical education. Do you think music is still seen as important in the education system today?

Yes, from what I've seen. I have three sons and when I look at their schools, all of them, the attention, focus and facilities for music has made a huge impression on me. I went to my middle son's school recently and when we looked around it I asked: "Do you have a school orchestra?" And they said: "Yes of course, let me show you where they play." He took me into a room and it was amazing. I said: "Do they give concerts in here?" he replied: "Oh, no. This is just the rehearsal room." I was blown away by the facilities. I've seen quite a few schools now and not once have I thought: "What a pity they've let music go." One of the problems about music is that when you're taught by a rather uninspiring, boring teacher who just wants to do things the classical way, there is nothing that will lose a child's interest quicker than someone who is like that. Teachers have to excite and inspire. My youngest son, aged 10, is naturally musical, has a strong sense of rhythm and has been fascinated by music from a very young age. I found that his piano teacher very quickly realised the sort of musician he is and when it came to school concerts encouraged him to write and perform his own pieces rather than saying: "You've got to play this one from the book." I'm very impressed with the musical opportunities today. Everyone has embraced music technology... If I have any concern about the evolution of music technology it’s that it's very dangerous in terms of making the samples write the music, if that makes sense. And what it takes away is 300 years of musical tradition and development because people are not looking at it any more. You can turn on a computer and have an instant orchestra without understanding what you're doing. Of course, there are people who will say I'm talking nonsense. They'll argue that's precisely what is so interesting because it's completely liberating. You can be grounded in musical tradition and still be modern. I listened to a very interesting interview with Quincy Jones recently, and I loved what he was saying about the fact that he feels sad that so much musical tradition is being lost and the result is that people are not writing proper melodies, they're not developing melodies, which is why there is so much bland music around. There is a lot of very bland music today. If I turn on the television it's almost like everything has come out of one box. Was it always your goal to have a career with music?

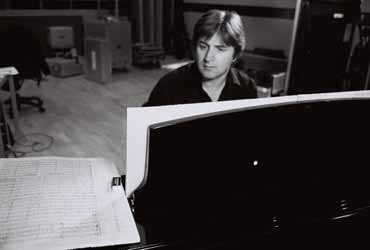

Yes. I always wanted music to be a career. I just didn't know how to do it. And I always wanted to write film music. The first piece of music I ever bought was John Barry's theme to The Persuaders, I bought the single. I loved the music of John Barry because I loved what it evoked. I loved the sound he created with music, the chords he was using and the space in his sound. I found it utterly engulfing, fascinating and evocative. I was lucky enough to meet him and spend three days with him in 1992 when he was recording his score to Chaplin, which was a life changing experience for me. It's a beautiful score, I spent three days in Abbey Road with him. What amazed me about the experience is that I had thought there was some technique he used to come up with the ‘John Barry sound’, but I realised it was all in the writing and his orchestrations. It was his writing that had created this sound, rather than some outboard piece of equipment. I once asked him how he wrote and he looked at me quizzically and said: "In my head. I write in my head." It's a wonderful way to write in your head, to hear the music in your head. Ennio Morricone does that. He'll sit in his study in Rome and wait for the music to come into his head putting it straight to paper. How do you write? Being a pianist, and having trained as a pianist, I've always written at the piano. When I wrote the choral requiem for Anthopoid, I wrote straight to paper which I found a wonderful and different experience. At school we had to write like this but technology has removed the need to do this. In a world where demos are required it is often faster to write direct into the computer producing sampled demos. I now find that if I can separate myself from the piano it makes my writing less pianistic... if that makes sense. It's very easy to be pianistic if you're a piano player and you're writing on the piano. I try and use my inner-ear to hear music in my head. You can work so quickly in your head, stopping, re-winding, dropping in, replaying in a single moment. I hear and pick up music or musical sounds easily and everywhere. I'm often inspired to the point where I'll use my phone to record a sound or something I hear. You know sometimes when you hear a piece of music and you only hear a certain part of it, because you're in a big building or there's lots of people and noise and out of that you hear something rather wonderful. Then you realise you know the piece of music well and that you were actually only hearing a few elements of it. It's almost like deconstructing the music to bring something else out of it. I love discoveries like that. I've been collecting scores for years. I can listen to a new soundtrack and straight away pick out segments that sound like a piece of music I haven't heard in years... right down to the name of the track. And when I go and check they are note for note almost identical.

Yes! You'll find so much of that. I remember I was working on Mother Teresa [laughs] and I wrote what I thought was one of the best cues. I came in the following day to listen to it and I thought: "Why is this so familiar to me? I've really written the most beautiful piece, but it's so familiar to me." [Laughs] and then I realised it was Mozart's Clarinet Concerto, the '2nd movement'. I had literally lifted every chord change and most of the melody, everything [Laughs]!.. such a disappointment to realise! I've enjoyed a life of music, I've been surrounded by brilliant musicians who've educated me, I've loved the work of all sorts of composers and musicians and what amazes me is when I suddenly listen to a composer whose work I haven't heard for a while and I realise how much of their music is in mine. Herrmann, Holst, Mozart, Beethoven, Rachmaninoff... There are so many examples where I think: "My god! I now know where this has emanated from." I suppose this must happen to every composer, except maybe the avant-garde composers, who hear things we don't hear and think so differently. When I compose, if I'm writing a big score, I often find there's a point where music is pouring out of me. I've opened up all the creative channels and I'm writing 2-4 minutes of music a day sometimes. I sit down and write, very quickly, reams of music. I think when you get to that point it's like being given access to a music matrix. It's like you can suddenly see the matrix of what music is. And when you're in that zone it's amazing the pieces of other people's works I come across when I'm simply writing; sitting down and improvising. I go from one composer to another. It might be Jazz, Classical, Pop. it could be anything. It's an extraordinary place to be. It's like riding the crest of a wave. You're suddenly completely in the musical zone. When you get to that point, when you're composing for a project, do you find yourself writing music that's not suitable for what you're currently working on, but that you can file it away to be revisited in the future? Absolutely. There was one point where I was scoring four or five films a year and I was writing the next score in the existing score because I was doing exactly that. I was writing music that actually wasn’t right for the score I was working on and then when I got straight into the next film I thought: "I'll go back and look at that." I quite like that actually, its fluid and creative. On That Good Night I sat down and just wrote for what I saw. I wasn't reverting to anything. I just thought: "I've got John Hurt and Charles Dance on screen. I've got a really strong cast here to write for, so I'll just be original for the film." There are other times where I just have to be inspired by something. I might not have the picture in front of me, it might not be finished.

I'm going to be writing music to a short film about the life of Douglas Bader, the Second World War pilot who lost his legs and then flew again in battle, a true hero. My head has already started work on it: How am I going to encapsulate what he went through in his life? There was a moment in his life, where having had this accident and having lost his legs, he was in hospital. There was a young nurse making a noise in the corridor and an older nurse said to her: "Be quiet! There's a man dying in there!". And he heard this and he realised they were talking about him. He suddenly thought: "There's no way I'm going to die." Things like that are incredibly effecting and very powerful and make you think. How do I do that musically? How do I find that strength in the music? A couple of years ago Bear Grylls did a live show about four incredible survival stories and I had to write the music to describe each one. He recited each story into his iPhone and the recordings ended up with me and I had to accompany his voice telling each story. I loved doing that. There was no picture it was just his voice telling these unbelievable stories of adversity and all I had to do was dramatise it all in the music. That was a great experience. Caldera want to release it as a score because it's very dramatic story telling. I know Caldera wanted to release Mother Teresa. It's very similar in style, I understand to Mary of Nazareth, which was released after it. It is. The producers of Mary of Nazareth were the same producers as Mother Teresa and that's why they hired me. It was a difficult experience because I'd worked with Giacomo [Mary of Nazareth's director Giacomo Campiotti] before for a different producer and Giacomo wanted one thing and the producer, who was very strong minded and strong willed, simply wanted me to carry on the score for Mother Teresa, seamlessly almost. But it was never directly said to me. I would have felt a bit strange carrying on writing Mother Teresa for an entirely different film. It's one of the things that comes up: "Who do you listen to?" Well, surely it's the director, he's the one whose conceived what it is he wants his audience to watch. But equally the people with the money, the producers, are very important. I was talking to a young composer recently who is scoring a television series. She asked: "How do I keep them all happy." I replied: "You've got to find a way." Producers control the purse and, if they have a strong musical interest, they may see things in a certain way that differ from the director. You do have to find a way of appeasing both. But ultimately I believe in working with the director. Have you ever walked away from a project because you didn't think you could work constructively with a director?

No. I almost did on Maria [Maria di Nazaret / Mary of Nazareth) because I was being pulled in two very different directions. How can you possibly deliver a score when one person very strongly wants one style and another very strongly wants a different style? How can you ever answer that? So I said: "Look, do you really think I'm the right composer for this? I'm not sure I can give you what you want." And they said: "Yes! Yes! That's why we've chosen you. Of course you're the right composer for it. You've got to do it." There was another film that I scored some years ago where we had a very long opening scene and I saw the film in one way and the director saw it in another. The opening scene was about 4/5 minutes long and it all needed music. Having seen the whole film and having talked to the director about it I scored it in the way I thought was right for it and it wasn't until version 8 - that's 8 completely different versions of an opening scene - that the director felt I'd found the sound he was looking for. I remember saying to my engineer at the time: "If I don't get this right, there's no way I continue on it". What about when you've composed music for a scene, and spent a lot of time getting it just right, and then they re-edit it? It's soul destroying. There's something about when you arrive at a scene and you score it fresh - this is why I've always gone on about trying to get a locked picture to work to - because there is nothing worse than having to take apart what you wrote originally to a newly edited version of the scene.... but its part of the process of film making and it’s about the film, not the music. You have to have the humility to realise that you're just one ingredient. Things change in filmmaking all the time and you just have to be able to accept that and just get on and problem solve. I often say to young composers today: "You may well be a composer and have a very romantic dream of what being a film composer is, but ultimately you are a problem solver. It's a given that you can give them a great product, but what they want you to do is be the least trouble possible, deliver everything on time, on budget and whatever problems they have, you can overcome them easily, amend and send through new versions." People think that you can just push a couple of buttons and lose 37 seconds off a scene. I often find it very difficult to go back and reconstruct something I've written that works so well with the way the scene was and then have to take out a minute of it... or even 10 seconds. I had it on something recently where I had to lose 10 seconds in a 60 second piece of music and it was the most important 10 seconds for me. It worked so well. In fact I ended up sending them two different versions. One which retained that 10 seconds but of course it paid a price later in the scene when it just wasn’t as good.

Sometimes you don't get scenes right the first time. And the director comes in and says: "No. No. This is not right. Why don't you try doing this. Could you start that later and can you do this here." And you do and you think: "Ah! That's much better." And then he comes in and says: "No. No. Give me even more of that." And then you realise that actually the director led you to scoring it the right way, the scene is better for it. This happens a lot at the final film mix where everything comes together and the creativity continues as music is edited, dropped or moved. Then there are other times where I believe so strongly in the way I've scored a scene that I can be accused [laughs] of bulldozing over what the director thinks. I think it's important, as a composer, to be confident about what you've done. Being arrogant is not a good thing, having humility is very important and realising that you're not always right... Do you prefer to come onto a project at the very start so you can get more of a feel for what the director's looking for, or do you work just as comfortably coming in once the movie's locked? I would always say the more time I've got, the better. I would say that when people have said: "Here's the script. Go away and write something", invariably I don't use what I've written because I react so differently when I see the picture. I've just been offered this film today, it's a biographical film, and they're in the editing room at the moment and I said to the director: "I would love to see the film when you have locked it, because then I'm seeing your vision in the form of a finished (edited) film." There's nothing wrong with being sent the script or scenes during the edit and discussing the film with the director, because it gets your head working straight away. I start thinking about things instantly. I go to bed at night thinking about it, I think about it during the day. I start storing ideas, almost subconsciously. But it really starts when the film is in front of me and I can sit down and watch it. If someone rings me up and says: "We've only got 17 days and we've just fired the composer. I'm sending it over to you now..." That just smells like problems. I've scored two films in a 15 day period. It wasn't huge amounts of music but it was a very tall order. What was the last piece of music that you heard that effected you?

Of someone else's work? Phantom Thread [soundtrack] by Jonny Greenwood. Instantly! I heard a couple of pieces and I listened attentively, immediately. I haven't been to see the film yet. I find Jonny Greenwood very interesting. I believe he was a viola player and had studied the music of Penderecki [Krzysztof Penderecki] amongst others. At the time when I scored The Broken, where I was inspired by some of the writing of Penderecki, Jonny Greenwood did the same on There Will Be Blood. I remember going to the cinema and watching the opening scene, the first cue came in and it was like listening to one of the cues I'd just done. I find him very interesting. I tell you something I did love. The score to Nocturnal Animals composed by Polish composer Abel Korzeniowski. I thought that was a really beautiful score. I enjoyed it so much I thought: "I could have written that. That's so me." The first album of yours I reviewed was Knife Edge [2009] and I couldn't believe that it was the same composer that wrote The Hot Potato because they were so different. Both enjoyable for different reasons, but not alike in the slightest. Do you try to choose projects that stretch you creatively? I want the listener to love the music, because that's what I've always known. I like doing very different projects. I'm very at home in the orchestral idiom because I get so much emotion out of a room full of players but at the end of the day I'm still the same composer. The effort is still the same with the way I wrote the music in Knife Edge, Modigliani and The Hot Potato. It's still me, normally in the same lightless studio [laughs]. Do you find it more enriching to be challenged by varied work than to be sat composing the same sound time and time again? I had a conversation with Thomas Newman about the soft piano in The Shawshank Redemption. I asked him: "How on earth do you go on reinventing that?" Because every film he was being put up for, they'd use the piano theme from The Shawshank Redemption as temp music. And yet, brilliantly, he managed to write further piano pieces of music that always stood up on their own. They weren't copies, or second rate copies of Shawshank. People talk about composers having their own voice. My sister says that she can recognise any of my music if it was played. She says she knows my sound. I'm not sure I do have a sound, to be honest. People think I do have a voice. John Williams has a voice, Thomas Newman has a voice, Bernard Herrmann has a voice, John Barry has a voice... All these great composers have their amazing voices. I always think that we're supposed to be able to write anything. When the producers met with me on Tsotsi the first thing they said to me is: "Can you write Kwaito music?" I didn't even know what Kwaito music was! So I said: "Yes, of course I can do that. That's no problem at all." '[Laughs] I had to come back and look it up [laughs] and then think: "My god! I'm in trouble, this is South African ghetto music." I didn't know the first thing about it but I was fortunate enough to know a couple of South African producers working in my studio complex and one had worked with quite a lot of Kwaito artists so I was able to work with him and make it dramatic for the film.

I like moving to different styles and different eras. For a long time my engineer was Adrian Thomas, who had worked with George Fenton for a number of years. He'd learnt so much from George Fenton that he passed onto me. He was the one who'd say: "Why not think about this differently rather than always reverting to what you know. Think outside the box. Think differently." So I've sort of prided myself on being able to do what's required for the film no matter what the style, but somehow retained integrity in the writing so that I'm still producing good pieces of music. I enjoy the journey of something new that might require different instruments than I'm used to using, especially world and ethnic instruments. John Williams's score for Memoirs of a Geisha [2005] is just beautiful. When I went to see the film I just couldn't believe the beauty of the music. I didn't know who'd written it and then at the end I discovered it was him, I almost dropped my shoulders in disbelief that he could be so good writing in that style, for those instruments, for the setting of the film. When I was writing on Mother Teresa, I worked with various Indian musicians who were all outstanding. But I had to do a lot of work learning about the various instruments to make them work effectively with the orchestra. I had to learn to understand those instruments and how to write in that style as apposed to writing cod Indian music. You did a similar thing for That Good Night, didn't you? Having a band playing Portuguese music as well as the orchestral score... Well, one of the things the director wanted in the music was the flavour of Portugal. He really wanted to capture that idyllic Mediterranean life that you can only imagine. And the obvious way to do that was quasi-Mediterranean folk music. I wasn't going to use original Fado or Portuguese folk tunes, I have done that before. I did it on a film called Dot.Com [2008] where I took three Portuguese folk tunes and I had my so-called Portuguese band play them. For ‘That Good Night’ I wanted to write thematic film music and record my themes using any instruments, orchestral or ethnic. It doesn't take much, you know. You can put a mandolin over an orchestral track and suddenly you've got the flavour of another world. The moment you move into recording the orchestra, out comes all the emotion. I have this great smile across my face the first time we run through a piece of music because suddenly it's become real. It's an utterly magical moment. How do you convey that to a director when all you've got is your original piano music to play for them? For example, for Modiliani how did you get the subtlety of the music across originally? The director didn't want me. He felt that I was being imposed on him by the producers. He wanted Elmer Bernstein. The editor, whom I knew well, said: "Just write something and let me put it in the film." And I said: "How can I? If he hears something that's come out of boxes (samples) how is that going to move him?"

I just happened to be doing a string session for a pop album at Sony Whitfiled Street and at the very end of the session I asked the musicians: "Would you mind playing this through for me and allow me to record it so that I can show the director what my theme sounds like live"... on the basis that if it was used everyone would get paid and they could play on the score. I must have had about 40 musicians and they were wonderful. We recorded it, I mixed it and handed it over to the editor and she put it over one of the most important scenes in the film - where they hadn't been able to find any suitable temp music. The director came out and said: "What music did you use over Jeanne's death?". And she said: "It's Guy Farley's. He wrote it for the film." And the director said: "That's it! I want to see him tomorrow. He's scoring this film. We've never found anything that worked over that, and that's it." I've done that on other occasions and it hasn't paid off [laughs]. It hasn't made any difference that I've spent my own money to get some musicians in to show something sounding good, just to have it dismissed in a second. Will we ever see a Caldera rerelease of Mother Teresa? The only person who could pull that off is Stephan at Caldera. He has the tenacity to do it. He has the determined character to do it. What he's got to do is get hold of the English and Italian producers and iron out whatever their issue is. It was all to do with music rights. It's interesting. I'm going to call him later and suggest it to him. It's brought up every year. There has to be a way it can be done. The music is sitting there doing nothing. I think they had one issue of 1000 CDs and it was sold out in something like six weeks. Every time I've brought it up with the English producers, who have moved onto other things, they say: "Yes, yes, yes." And then I don't hear anything and the Italian producers say they can't give authority to do it and it just keeps going round and round. I'm prompted by what you said. There's definitely a possibility. Part of me thinks we should just release it... and so what [laughs]. What are they going to say? Do you now try to ensure that you can keep the rights to all your soundtracks, wherever possible?

It's a conversation I always have. I find that the film companies are very happy to have this extra advertising. "A soundtrack release? What a lovely idea. As long as we don't have to pay for it, we're happy for you to do it." The only people who are tricky to deal with, because of their systems or bureaucracies, are the Italians - and I just happen to have done half a dozen Italian films. They're just very slow and very stuck in their ways. Stephan has done it, L’uomo Che Sognava con le Aquile was released on the back end of one album [Maria di Nazaret]. So it is possible, just someone has to do it and keep up the energy. What would you say are the best and the worst aspects of your job? There is nothing quite like the moment you walk out and stand up on that rostrum with an orchestra in front of you and then you hear what you've written. It is one of the most fulfilling things I've ever experienced in my life. Does that never diminish? No, it never diminishes. It's just an amazing experience. It's utterly engulfing, rewarding and fulfilling in every sense. The worst side of it is that it's always painful at the start of the scoring process, although it's become less painful over the years, because you're being very vulnerable when you write for people. You're exposing yourself. That's always difficult, but everyone experiences that. I think the worst thing is, and I can't remember the last time that this happened, when somebody doesn't get what you're writing and then they start pushing you to write like someone else. That's really painful. I had one instance in one film where the director ended up using half of one of Martin Phipps's cues and half of one of mine, because he was so wedded to the temp music. It's awful when you end up in a situation like that. Either that's because I've failed as a composer to write what the director wants, or he's just pushed me into a place where I'm copying someone else's work and I can't stand that. I think the most painful part of it is when you can't be free as a composer. You need to be free to compose, because if you're not what are you? You're just a puppet that someone's using like a jukebox to churn out someone else's music. What a failure it is when a director can't find a composer to write an original piece for his film that he has to go and get someone else's music in or get a piece copied. Temp music is there to find the right emotion and beats for the scenes isn't it? Can you use that as starting block or is it too distracting...? Temp music suddenly makes what they're editing sound real and expensive, it also provides rhythm for cutting and instant emotion. Suddenly it makes their film sound fantastic. If used properly, by an experienced music editor, it's really useful because you can score a whole film and decide on your score starts and ends, what works, what doesn't work, instruments, sonics etc... There are lots of good things about temp music if it's used properly. The worst thing is when people fall in love with it. That makes a composers job almost impossible. What do you write when someone's already in love with something that's already been used in something like American Beauty? How can you possibly compete with something like that? Do you find that difficult working on several projects at one time?

No. I quite like it, actually. I think my work span on the biographical film will be over six weeks and sometimes it's very good to have a break in that, but I'm very disciplined at my work. Time management is extremely important and I find sometimes it's important to have a short break. I will be transcribing a Russian piece of music for The World Cup. It's a beautiful piece of music and I love doing things like that. I get asked to do these transcriptions of these beautiful pieces of music and then go in and record them. It's like an incredible lesson into taking apart music from the past and recreating it. You discover things and you learn all the time doing that. I am most happy when I've got a really powerful, evocative film with good performances. I love just watching and then finding my way and developing a relationship with a picture in front of me. That's where I'm happiest writing. I found it a surprise to hear that you had problems writing a theme for John Hurt's character in That Good Night because you hated him so much. I didn't like him. This is a story of a very difficult man, a very selfish man - a bully in a way - who is told he's terminally ill and tries to take his own life, because he's always been in control. I didn't like the way he was with his wife, with his son and the way he lived. He was just a really obstreperous unlikeable man, so how could I write something for someone I didn't care about? How could I do that? I didn't like what I was writing. It just felt like I was being dishonest. I found it easier to write the other music, like where the film is set and to write for other characters. It took me a while to get into it, actually. Firstly I rang the director and then I rang the writer and I found they'd had a similar problem. How could you care for someone who wasn't likeable? But in the end, both the writer and the director made me see that actually he was an honest person but he was just blunt about what he believed in. And the fact that he survives his suicide attempt and remains alive long enough to see his grandson being born, it does change him. I had to find a way of tapping into that early on. I'm happy with the way I've scored it. I think I've got it right. Everything I write is always my reaction to picture. It's always what I feel. I care about the music. I really do. I care about the quality of it, the sonics of it, the production of it, the engineering, the musicians... every single aspect I care about. The bar is set by people like John Williams, Thomas Newman and the teams they use. Is there ever enough time and money to get the finished product how you want? I don't care about money. I'll do whatever it takes. I don't mean that flippantly. I've never done things for money. I've always used whatever I possibly could to try and make it better... even if it's cost me personally.

Time is a problem, yes. And if I can't get into the right studio and the right room then I have to work really hard to get it to sound right. But somehow we do. I think it's always a bit disappointing if you want a really big sound and you're limited by having a small number of players in a small room. You end up trying to fake the sound of a big orchestra, I think on Angela's Ashes [John Williams], you could argue that it was a bit big for the film, but the music is beautiful. I want my music to stand up like that. I think I have an absolute duty to aim for it. There won't be another John Williams and there is nobody like him. I was devastated when John Barry retired from scoring the Bond films, because they felt flat for me; every time without fail. He was the sound of Bond. Having said that. John Barry would be totally wrong to score a Bond film today because his Bond scoring was too humorous, too bombastic, too over the top and they've got serious now. If a movie were to be made of your life, who would score it? Wow! There's a question. I like Abel Korzeniowski. I would ask him. I don't feel important enough to say John Williams, John Barry or Elmer Bernstein... I don't really buy modern scores, but I thought his work on Nocturnal Animals was really beautiful. The other composer whose work I love is Wojciech Kilar... and Gabriel Yared - there you go. There's three. I wouldn't feel worthy of Gabriel Yared or Wojciech Kilar, but I sort of feel a kindred spirit with Abel. There was something in his music that I really connected with. I found myself in it, if that makes sense. Can you tell us what you're working on at the moment. As usual I'm working on a number of different projects. I'm currently talking to a director about a biographical film, which at the moment looks like it's going to be a BBC production. It's about Sylvia Plath’s book The Bell Jar. In her life she suffered from terrible depression, eventually committing suicide. It's a very powerful story. I'm also scoring a short film on the life of Douglas Bader, which will be performed live as well. I'm always working on other bits and pieces. I'm transcribing a well known Russian piece of music which I'm going to record with a Russian bass-baritone and I'm doing some music from The Wizard of Oz.

Click here to visit Guy Farley's official website Click here to keep informed of Caldera Records' latest releases This interview was conducted on 19 March 2018 Return to... |

|---|