|

Click here to return to the main site. Book Review

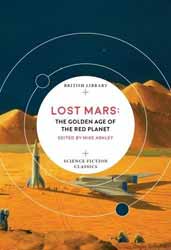

From the earliest times of man, there were always celestial objects which were detectable by the naked eye. Although both the sun and the moon were obvious candidates both Venus and Mars are easily seen. As such these unknowable worlds became objects of fascinated imagination. Lost Mars: The Golden Age of The Red Planet (2018. 303 pages), edited by Mike Ashley, collects together some of the best short stories related to our nearest planetary neighbour. The book has a twenty-page introduction by Ashley which presents a definitive brief history of Martian science fiction which covers a lot more ground than a retread of Well’s War of the Worlds (1897), possibly the most commonly known story regarding Mars, or at least Martians. Man has had an intimate relationship with Mars. What was first an object of fanciful speculation started to come into sharp relief with the invention of the telescope. With this, the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli erroneously thought he saw canals, which spawned a whole genre of Martian literature imaging what civilisation and forms of life built them. Of course, he was as wrong as a flat Earther, Mars is essentially dead. The knowledge of this change meant that, over time, much of the literature transformed from its early twentieth century romances to stories of death and survival. Suitably, the collection opens with The Crystal Egg (1897) by H. G. Wells. Written as a journal, it tells the story of a nondescript dealer in Antiquities who has come across a curious object. When one looks through the egg it shows another world. It’s a fanciful piece which attempts to show the strange beauty of Mars. It’s a piece of romantic fiction and a precursor to the more elaborate works of Edgar Rice Burroughs. Letters from Mars (1887) by W. S. Lach-Szyrma is the first of the stories which directly incorporates Schiaparelli's idea of Martian canals. Written as a travelogue it was part of a much greater body of work. Lach-Szyrma used the idea of a planetary explorer, Aleriel, to depict his idea of the thriving culture of Mars. Aleriel spends time around the Martian poles which feeds the canals before finally travelling down into the lowlands and the detailed description of the canals themselves. Although Well’s had famously depicted the Martians as hostile, the consensus of popular fiction was that such an advanced civilisation must be benign. Not having destroyed themselves in some atomic holocaust they must have reached a level of technological and spiritual development far ahead of our own. In The Great Sacrifice (1903) by George C. Wallis tubules start to fall all over Earth, while at the same time the outer planets start to move differently in their orbits. It takes a little time but eventually the tubes are deciphered. They tell of a swarm of meteorites heading into the solar system with a circular orbit of twenty million years. So large is the mass of rock that it soon becomes clear that it represents the end of all life on Earth. What follows is a two-part description. Those who fear the end of the Earth either crowd the churches or loot. Cooler minds hope that the Martians are doing more than signalling the end of mankind. P. Schuyler Millers story, The Forgotten Man of Mars (1933) sees the stories move into the golden era of the great pulp magazines, which under good editors, tried to keep stories on a more scientific footing. Of course, some suspension of imagination was still required in order that a survivable atmosphere could exist on the surface. Millers story is more akin to Robinson Crusoe, as the main character is abandoned on the surface, only to be adopted by the Maee, an indigenous life form. Stanley G. Weinbaum’s A Martian Odyssey (1934) uses the motif of another lost and stranded Earthman to explore the sort of ecology which may exist on our near neighbour, from silica-based life forms trapped in an endless cycle of pyramid building to a bird-like companion whose thought processes are so alien that communication is near impossible. If Well’s made a significant impact on how we viewed Martians, then Ray Bradbury made an equal contribution with The Martian Chronicles (1950). More spiritual than Well’s vision, Bradbury series of linked ‘future history’ short stories tells of man’s colonisation of Mars. His Mars still has an advanced civilisation, which is destroyed by invaders; man. In a nod to Wells, Bradbury has the Martians destroyed by germs brought by the first astronauts. Ylla (1950) was the second chronicles story and tells of a Martian woman who dreams of the coming of men. Each night she dreams and each time as she tells her husband he becomes increasingly jealous of her attachment to this idea. When the Earthmen finally arrive, her husband reacts with a surprisingly human emotion. Marion Zimmer Bradley was one of those writers whose view of Mars harkened back to a more romantic earlier age. In Measureless to Man (1962) even though it had been proven that there were no canals and no advanced civilisation that we could see, she nevertheless still dreamed of finding some illusive remnant of the Martians. In her story, the protagonist, Andrew Slayton, is part of an expedition to reach what could be the last remaining city on Mars. All who have tried have gone mad, died or murdered their companions. By a strange quirk of fate, Slayton meets the disembodied essence of a Martian… If Bradley clung to a romantic past with E. C. Tubb this is all but swept away. Without Bugles (1952) shows a world of dust, which slowly kills those who try to work in it. But even in this hell hole Tubbs presents a story of men overcoming their own fears and limitations for a greater tomorrow. By the time Walter M. Miller Jr wrote his Crucifixus Etiam (1953) the Martians are truly dead, never having come into existence. Yet the planet still has hope for a new tomorrow. Miller turns to science to bring the long dormant orb back to life. The last story in the collection, The Time Tombs (1963) is from one of the greats of modern science fiction, J. G. Ballard. Like many before, he cannot escape the romanticism of discovering some remnant of our lost cousins, though unlike the gung-ho of previous protagonists Ballard’s main character has more in common with Bradbury’s more thoughtfully sensitive Earthmen, with a distaste of robbing tombs. It’s a good collection reflecting the ever-changing relationship we have had with our nearest neighbour, from the hopes of finding life to the reality of Mars as a dead world. 9 Charles Packer Buy this item online

|

|---|