|

Click here to return to the main site. Blu-ray Review

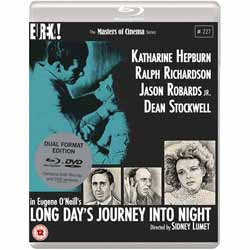

Gen X, Y and Z audiences will no doubt sniff at Boomer and Cro-Magnon praise of Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night as the greatest of all twentieth century American plays as so much proffering a load of cobblers. As long as geezer discreditation is at wrinkled hand then let this reviewer add, it’s probably the greatest twentieth century play of the world. It has been transposed into multiple cultures and languages and performed and filmed so many times the Wikipedia history takes awhile to read and longer to absorb: wikipedia.org/wiki/Long_Day%27s_Journey_into_Night It was O’Neill’s family autobiography, so painful he left orders for it not to be unwrapped and performed until twenty five years after his death. His widow waited two years then opened this dramatic Pandora’s box and it has been produced and performed almost constantly to this date. Somewhere right now (maybe with a little adjustment for Covid-19 time) someone is planning the next performance. The 1962 Sidney Lumet/Boris Kaufman collaboration is the archetype all other productions bounce off of or alter radically or faithfully try to emulate. The latter course is hard to envision even for au current geniuses, so iconoclasm has usually seemed the safer compass point. One of the best alternative approaches was the Jack Lemmon production in 1987 which took on the rich dialog not by rewriting it (as some hubris heads have been led to do!) but re-executing it from the inside out with overlapping and simultaneous dialog, giving it a naturalesque buzz. The Lumet production is theatrically traditional with rapid fire machine gun delivery but always maintaining sequential linearity. The Lemmon production sounds more normal. The Lumet more theatrical. Boris Kaufman’s cinematography follows a single day in the life of the Tyrone family in August 1912 with its shadows and angles sharpening as the day progresses and falls into night. This is archetypal black and white imagery, reminding us that tone is mood and shade is light adorned with soul. Kaufman’s deep focus wide depth of field expands beyond anything Greg Toland did for Orson Welles in the razzle dazzle of Citizen Kane and makes its points with subconscious subtlety. Its realism is grindingly overwhelming. We are awash in full focus frames of a two dimensional picture when our eyes never see daily three dimensional existence without rapid nano moments of follow focus. We are impelled by the unreality of Kaufman’s wide depth of field to read its avalanche of detail near and far as super reality when “in reality” our minds are constructing a psychological “impression” of reality described by artistic ocular nonreality. The contradictory result here is domestic family life gravitas. In most film noir this is pulp psychology. With Boris Kaufman lensing Eugene O’Neill it is classic humanity. We cannot neglect mentioning the Andre Previn music track, his solo piano score, atonal, not written in any key or mode, ignoring conventional harmonies altogether, establishing instantly, shockingly a staccato slammed urgency, annealed with unresolved compacted anger and anguish. And beneath all that, a deep tidal grief. Previn’s discretion and choice for O’Neill’s cosmos is one of the most unambiguous musical entrées ever and one of the most memorable atonalities in all film music. But to be truthful, something you won’t find yourself humming in the shower. (For Previn consultation here I must thank musician/composer Mark Costigan and muse Coco Cotes Rowland.) Lumet knew his cinematographer and composer and let them do the art they knew best. With his cast he collaborated to get their best, knowing that directing is ninety per cent casting. It is probably Kathrine Hepburn’s best performance ever, a tough call in light of The African Queen, Philadelphia Story or, my favourite, Suddenly Last Summer. She came out of retirement for the role of Mary Tyrone, the morphine addicted matriarch and worked so hard the psychic pain is evident. She is every age in this, consummate, simultaneous, aware. Ralph Richardson, James Tyrone, has the difficult task of playing a grandiose nineteenth century stage star who has sold out by playing one role all his professional life (O’Neill’s father played Dumas’s The Count of Monte Christo six thousand times) so, at home the ham is never far from the table even when the heart is broken. He has acquired material wealth at the price of being a miser to his family. Their oldest son, Jamie, Jason Robards Jr., is in his mid-thirties and already an alcoholic and anti-social saboteur of any chance for success. He is the Tyrone family’s provocateur and seeming conscience which is, after all, a lie to disguise his jealousy of his younger brother Edmund. Dean Stockwell’s Edmund is seemingly the most pale and delicate of the quartet. This is a mistake often made by critics. Stockwell’s work from childhood on is marked by performances etched with internalised veracity. His believability here is easy to discount. He is the pivotal character who will be more changed than anyone else by being a witness/participant of this story. Edmund’s tubercular weakness and surface timidity is a family role of the puer aeternus, C. J. Jung’s category for the typology of the child man, the child who is perpetually emotionally and psychologically sensitive to the passion of perceiving. Edmund is already showing talent as a poet and writer. He is the stand-in for O’Neill himself and whose greatest work will be this autobiography he wanted to stay buried with him. So what happens in this four act day in the life of the Tyrone family? Truth. Truth that everyone already knows and knows everyone else knows, finally spoken aloud in same room together. Truth as critical mass. Truth breaking through the compartmentalization of family hiving. All families compartmentalize. Only sociopathic mendacity can deny this. And only fools rush in to try. Fools with something to hide. O’Neill takes no prisoners whether one is a Gen X, Y or Z, Boomer or holier than thou aged one. Believe it or not, he loves us all. But love opens us to pain and that is the human journey he can’t save us from. We’re all on our own for this trip. The Eureka 1080p image does more loving justice to all artists involved than any preceding presentation. Brand new video essays, a collector’s booklet and audio commentary remind that O’Neill is alive and well with us in his work and entering his second century of reign. Oh of course there are a few other contenders for the crown. We should have a refreshment and debate that sometime. Some reviews on Amazon find Journey tedious, dull and over long. I understand. I’ve always felt the film incredibly hurtful to watch. Maybe that’s the Edmund in me. But I’ve always come back to it. Maybe that’s the Jamie in me. Sometimes pain is good for my growth as an existential human being. I guess that’s why I’ve kept returning through the tears to a long day with the Tyrone family. Mary and James make scintillating conversation around the dinner table. They’re never boring. Scary maybe but never do they effing bore. This Eureka edition is the best yet I’ve experienced. See it on a good screen worthy of the work that went into this home entertainment physical media gem. 10 John Huff Buy this item online

|

|---|