|

Michael

McAlister has worked in the movie visual effects business

for almost 30 years, cutting his teeth working on The

Empire Strikes Back (1980) as effects unit assistant camera.

Over the years his work has been seen in E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial

(1982), Return of the Jedi (1983), Indiana Jones

and the Temple of Doom (1984), The Goonies (1985),

Willow (1988), Die Hard 2 (1990), Waterworld

(1995), The Truman Show (1998) and Road to Perdition

(2002). Darren Rea caught up with McAlister as his latest

project, Eragon, was due for release on DVD...

Darren

Rea: How did you originally get involved in this industry?

|

Sci-fi-online's

little helper, James Field, gets the chance to ride

Saphira

|

Michael

McAlister: I got involved in the movie business quite by accident.

I never imagined how movies were made. I was never curious

about it - I'd never even taken still photographs before.

Before

I was at film school I was in engineering school, and I got

really bored with engineering and I didn't know what else

to do. One day I happened to met someone who was in the film

department at the school and started talking to them and I

thought: "That sounds kinda interesting. Maybe I'll try

cinema." And so that's literally how I got involved in

the movie business.

I

changed my major to film and worked on a project that this

guy was doing at film school. I realised that I loved cinematography

and from there I discovered special effects. I was in film

school when Star Wars came out and all of a sudden

visual effects was seen as interesting. So I started in that

direction.

It

was a twist of fate. The way I met the person from the film

school was that I walked home a different way one day to explore

a part of the campus I'd never been on before. A lot of times

when I'm talking to a group of kids and they ask me how I

got into the movie business I tell them that I turned right

instead of left. And that's literally true.

DR:

Is this industry suited to a certain type of character?

MM:

I think it is.

DR:

What sort of people make the best visual effects people?

MM:

One of the things that is really important is that you have

to be self-motivated, because the work is really really hard.

It requires a lot of hours and if you don't have the reward

within yourself for a job well done, you're probably not going

to survive.

At the end of a long project there is always lots of praise

and lots of accolades, especially when the job's well done,

but along the way it gets really tough and you just need to

be okay within yourself, knowing you did your best even if

the praises are coming in.

So

being really strong inside yourself, in terms of being motivated,

is important. But also it's really great to have an idea about

artistic things - be able to draw, even if it's within a computer,

but to have an idea of aesthetics - to be able to look at

the world and see what makes the world look real to us. Most

of what we do in visual effects is just create illusions all

the time. In order to get away with it you need to know what

reality looks like. For instance people that want to be in

visual effects could do photography or study human anatomy.

Perseverance

is a great quality to have. Many times I'm talking to kids

and they ask me how you get into the film business. I tell

them that I think the most important think is to always do

your best at whatever job you are doing.

What

is most important to a guy like me is that I know I am hiring

somebody who will always do their best job. And if it just

turns out that they are not very good at that job, then maybe

they're really good at this job. But if you won't do your

best, because you don't like the job you are doing, that's

what I am going to remember - because you'll only do your

best because you like what you are doing.

We

don't always like what we are doing. In order to make world

class visual effects you have to do your best whether you

like what you are doing or not.

DR:

You've

been working in this industry for years movies for years and

must have tackled almost everything. Was there anything new

that you did while working on Eragon?

MM:

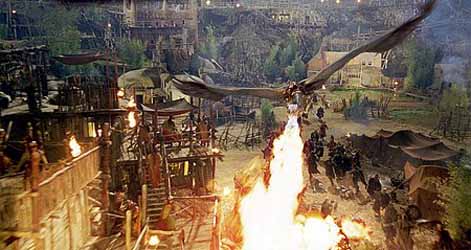

Eragon was the first time I had been responsible for

making a whole character from beginning to end. I've worked

on many movies and I've done little bits of creatures, or

characters, for little moments in films but this was the first

time I'd ever been involved in making a complete lead character.

It

was a whole different mindset - a whole different approach

to the work, because personality and character became a really

big part of what I had to concentrate on, rather than more

on the technical and the scientific end of things.

It was much more about human qualities and trying to figure

out how to use all the CG tools we know how to use to actually

create a real credible creature that is essentially human

in it's appearance and emotions.

DR:

Where did you get your inspiration from when you were creating

Saphira?

MM:

I studied a lot of things. I studied a lot of animals. I studied

a lot of big predator birds, just to get an idea of how Saphira

would move when she flies. And for when she's on the ground,

I studied big animals - elephants, rhinos, big cats, lions

and such. But I also studied human performances.

I watched actors, specifically female actors, and I watched

to see how it is they do what they do with their faces, because

human performances are often very very subtle. We as humans

can recognise emotions in human faces when there are very

subtle changes in their expressions. Until this movie I never

really paid much attention to what those cues are in terms

of your eyes, your mouth and your cheeks.

I also studied some of the work that went into King Kong

[2005], because King Kong as a character, and Gollum [Lord

of the Rings] as a character, are I think two of the greatest

animated characters ever in movie history. So I watched those

movies, especially Kong, because there are some moments

where I was convinced that he was a human wearing gorilla

clothes.

I

realised that we were making a really unusual character because

there's never been a dragon in a movie ever that is like Saphira

- who is lethal and very powerful as well as very emotional

and very feeling. She has attitude and things to learn.

So

I realised that no matter how much I looked at other movies

no particular performance would - whether it was a human performance

or Kong or Gollum - none of those were going to be exactly

what we needed to do.

I was able to learn about animation and learn about how to

create emotional performances in animated characters by looking

at those. But Saphira really became her own character, her

own personality.

For

me the most difficult aspect was creating the inner life of

the character. So that when you looked at her, especially

if it was an emotional moment, and you look at her face then

she looks as though she's about to cry. Or that she's really

hurt, or that she's a little bit angry, without it being cartoonish.

It's easy to do those things when you are making a cartoon

because you just make really big expressions and they growl

or something. But that wasn't our character. Our character

needed to be more restrained - she needed to hide her feelings

a little bit.

It

was a difficult and fun process of figuring out how big to

go with the expressions, and what expressions - what would

the things be that would communicate that she's hurt?

The

other thing that was challenging for her was the balance between

her animalistic qualities and her human qualities. We didn't

want her to be so soft that she was just a human that couldn't

turn around and bite your head off in the next moment. We

always needed to wonder about her. If the anger comes out

is she going to start burning or eating people?

DR:

What's the one visual effect that stands out most in your

career - the one time when you really nailed it on the head

and still makes you proud.

MM:

There are three films that I think I am most proud of. One

of them is The Hudsucker Proxy [1994 - McAlister was

the movie's visual effects producer], and the reason I am

very proud of that film is because there's not a frame in

the entire film that I would change. It was difficult to make

in those times because we didn't have all the computer tools

we have now. But I thought it was as perfect as anything I've

ever made in terms of what the director wanted.

I'm

also quite proud of the work in The Truman Show [1998

- McAlister was the movie's visual effects supervisor]. Neither

one of those are particularly effects driven movies. And I'm

also really proud of the work on this movie, Eragon.

I think that Saphira is a tremendously good character and

she looks great.

Then

there are other big effects movies I've made include the mine

car sequence in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom

[1984- McAlister was the movie's chief visual effects cameraman]

has always been a favourite of mine and the crashing aeroplane

in Die Hard 2 [1990 McAlister was the movie's visual

effects supervisor working at ILM].

Actually,

that's worth thinking about a little bit, because I haven't

thought about that in a really long time.

DR:

As a visual effects supervisor do you get much input into

the creation of the film?

MM:

Sometimes we do. By the time special effects people get involved

in the movie the script is pretty much what they are going

to make. Every once in a while our expertise can be used in

a way that creates possibilities that the writers or the director

weren't aware of - happens all the time these days.

Some

times visual effects people will come up with ideas for movies

and they'll get the chance to actually make the movie. There's

another effects supervisor, I've just heard about a couple

of days ago, that came up with an idea and he's going to direct

a movie for Disney.

Stefen Fangmeier [Eragon's director] was a visual effects

supervisor before making this movie, so it happens from time

to time. It mostly depends on us and whether we want to do

that. It's a lot of work to direct a movie - you have to be

nuts.

DR:

Who's been the best director you've worked with and why?

MM:

The man that had the most influence on me is Peter Weir. I

did The Truman Show with Peter.

One

of the things I noticed about Peter, that impressed me so

much, is that firstly he's extremely well prepared when it

comes to the set. He has a really good idea of what he really

wants to do with his scene and as he's directing the scene

if it isn't working for him he'll throw the whole thing out

and start over with another idea.

That

really impressed me because one of the things I had done in

my approach to work up until that point is I would fight against

the fact that something wasn't working and I would try to

make it work anyway.

I

did a lot of second unit work for Peter on The Truman Show

and there was one moment where I was directing this scene

and he came by to see how it was going and I was just struggling

to make it work.

He

said: "Can I try something?"

And

I said: "Sure, please help."

And

he throw his vision of it out, my vision... he threw the whole

thing away and he started from what was actually taking place

on the set.

What

I learned from him was to pay attention to what was actually

happening more that what I thought I wanted to happen. Sometimes,

in a perfect world, you envisage it so well that it actually

goes the way you thought it would. There's some things in

the Truman Show that nobody could ever have thought

of in advance, but they just happen right in front of him

and he was aware enough to pay attention to when that was

happening.

That

was probably one of the biggest lessons I've every learned

from a director.

DR:

We often hear about the nightmare that actors have when acting

on a blue screen - that they are acting to nothing. What's

it like from your perspective? Is there anything you can do

to help the actors?

MM:

That's a great question and my job, as a visual effects supervisor,

means that I always assume some of the responsibility - given

permission from the director and the producers - to help the

actors visualise what it is they are doing in the scene.

On

set everyone is really busy just trying to get the scene made

and the poor actors are sometimes out there acting to a tennis

ball. The more that I can share with either the director,

who then talks to the actor, or directly to the actor - the

more that the actor can be made aware of what is going on

emotionally between these two characters - the better the

whole scenes going to be, the better the CG character will

look and the better the actor will look because they will

actually look like they are acting together rather than two

separate performances that are put together.

Some

of the ways we can help visualise is through drawings and

illustrations of what will eventually be in the frame. We

can go much further than that without spending too much money

doing something that's called an anamatic. This is a very

quick cartoon version of the whole scene and in this movie,

for instance, we would do a quick version of Saphira going

through whatever motions and emotions she was going through.

Mind you, we weren't really able to do that very often before

Ed

[Speleer] had to do his work, because we would photograph

Ed and then put the animation of the dragon into the scene

with Ed. But even before we photographed Ed sometimes we would

animate cartoon versions of a whole sequence so that everybody

would know what ultimately was happening. Ed

was pretty phenomenal at imagining what was going to end up

happening.

DR:

Was it easier working with a director whose background was

in special effects?

MM:

Yes, because we could speak in short hand because we both

know what we are talking about.

Sometimes

it's really challenging working with a director who hasn't

done visual effects before, because sometimes it's really

hard for them to imagine the possibilities because they don't

know what the technology is and they don't know what can be

done.

But,

with a director whose already done special effects for ever

and ever, they already know, so it's a question of what do

we want to make? It isn't about how will we do it, or what

needs to be done on set, because he already knows.

DR:

If you were given the choice what would you love to work on

that you haven't tackled yet?

MM:

What I dream of creating are human characters more than creatures.

Some guys who do my job just love monsters, and some guys

like doing cartoon characters, but I tend to like humans most.

That's why in my resume you'll notice that most of the movies

that I've done haven't tended to be the sort of movies that

are heavy on the creatures, whereas other people mostly work

on creature movies. It's just how I grew up.

DR:

With computer technology constantly being improved what do

you envisage for the future of visual effects?

MM:

Well, these days, absolutely anything that we can imagine

is possible to do. And that is such a blessing, such a privilege

to be working in this part of the business now.

I've been doing this for almost 30 years. When I first started

there was no such thing as computers, no such thing as motion

control, or computer animation. We just didn't use computers

and there were all sorts of things that you couldn't do. You

couldn't do visual effects that had water in them or fire

or smoke, and so growing up in the business there were so

many things you just couldn't do. Writers would write certain

things and you'd have to tell them to go and rewrite it because

we couldn't do what was required. Now we don't ever have to

do that, so they can dream anything up and, as long as they

have money to pay for it, we can make it.

In

terms of staying current with what's possible, it's impossible

for a guy like me to know all the things that are possible

to do any more, because there are thousands of people all

over the world that are inventing new software and new ways

of doing things and usually what happens is some writers,

or directors, cook up these crazy ideas that they would like

to see in the movie and then they hire a group of people to

figure out how to do it.

That's

when the new tools get created - it's all driven by some imagination

that somebody has of something they want to have in a movie.

Then us people get together and figure out how to do it and

then there's a new tool. But unless you were the person on

the movie doing that particular job you're not involved in

creating the tools, and you have to learn about it afterwards.

DR:

Who would you say is at the forefront of pushing the technology

at the moment?

MM:

WETA. WETA has done the most spectacular work in recent years.

What they did with their characters of Gollum and Kong is

truly remarkable. Like I mentioned earlier, they are the closest

that I've seen, in a movie, of a character that's real. You're

not looking at creatures, you are looking at people with full

emotional lives.

I think one of the ways that they achieve that is that they

had an actor perform Gollum, the same actor that performed

Kong, who took ownership and responsibility for that character

as any actor would do for any other character in a movie.

And that was the first time that anybody had done that and

it made a huge difference. The actor, Andy Serkis, was involved

at the beginning of the movie, he was there performing that

character on the set - obviously he was replaced with the

CG animation - and he was around afterwards talking to the

animators and helping them understand the emotional undertones

and overtones of being this character.

That's

really important, because when you create an animated character,

like the dragon or other characters you see in a movie, it's

not just one person that's created that. It's lots of animators

and they all put their own personalities into it and they

look at themselves in the mirror while they're animating to

see what it is that their faces are doing.

And so as good as the characters have been up until Gollum

and Kong, they were still kind of an accumulation of different

artist's talents - not one person's vision. So it was a real

break through when WETA did that.

The

most fun thing for me about creating Saphira was that while

there were lots of people involved in the creation of that

character, there was only me that was ultimately responsible

for choosing what she would do in every moment of every scene.

For

the longest time we searched for what her character would

be, because we borrowed from certain animals, she had to be

lethal and she had to be dangerous and she had to be loving

and kind and she had to have attitude - she gets mad sometimes

and scared other times. Trying to figure out how to create

all that was a really big job and mostly what I did on the

movie, as it turns out, was pay attention to her. After a

while I started talking to her as if she really exists instead

of talking about her.

Then

she started telling me what she wanted to do in scenes.

So we'd try certain things and it was as if she were looking

over my shoulder saying: "I don't do that. I would never

blink my eyes like that." So I would tell the animators

that she doesn't blink her eyes like that. Or she doesn't

turn her head a certain way and after a while it became really

easy for me because she became so real in my imagination that

I didn't have to think about what she would do any more. She

would just tell me. It was very difficult to communicate sometimes,

but it became very easy to recognise her.

I

learned about animation from one of the best animators in

the world, Phil Tippett. When I first started my career I

was working with him and Dennis

Muren and I would watch the way that Phil Tippett

would create characters. He would act it out with his body

and he would feel what it was like to be the characters and

then that goes through kind of a translation into the physical

shape of the body that is being animated.

My

body doesn't look anything like a dragon, but if I would get

on the ground and I would move the way that I imagined the

dragon would be moving, what that does is it teaches me what

it feels like to be her in that moment.

At

one point when we were shooting I was sharing an office with

a whole bunch of people and there was this open space in the

middle and I just got down on the floor and started crawling

around and feeling what it was like to be Saphira in this

moment. And, when I'd finished, I looked up and everyone was

looking at me like I'd lost my mind because they'd never seen

anybody do that before.

The point of it is they told me I looked silly, and I probably

did, because there's this human trying to be a dragon and

I don't have all the right parts, but it taught me what it

felt like. So then I could imagine other things, like what

it feels like for her to be in this moment so what do I need

to do with her body in order for the audience to get that

feeling.

|

The

shot that I specifically did that for is the shot where she

is saying goodbye to Brom after they've buried him on the

top of the mountain. She bows down to say goodbye to him.

That was a moment in the movie that was created sort of inside

me first by feeling what it would feel like for her to say

goodbye. And then it was like: "Okay, so that's what

it feels like. How do we show it?" I actually borrowed

from the religion of Islam for that moment. I remember seeing

the way that Islamic people pray - they go all the way down

to the ground and put their foreheads on the ground and then

they get up again and do it again. There's something really

reverent about that. And so I put that into that shot.

DR:

If you could go back in time and give yourself one piece of

advice what would it be?

MM:

[Laughs] Not to take myself so seriously [laughs]. There was

a time when it felt like life or death to me. I was very young

when I started in this business and younger people tend to

take everything as if it's a life and death scenario. It's

just taken me 25-30 years to learn that it isn't life or death

- that you do your best work and if it isn't working out it

probably isn't because I'm not good enough, it's probably

just because it's really, really hard.

Nobody

ever told me that I had to sort of figure it out. It took

about 20 years of beating myself up to figure out that it

wasn't me. It's just that it's really hard at times.

DR:

What are you working on at the moment?

MM:

Right now what I'm doing is taking a tour of the world looking

at all kinds of smaller visual effects facilities in Europe

and India that might want to play in big movies, and then

after that there's a number of projects that I'm looking at

- I haven't quite decided what to do yet. I know that I would

love to do another CG character - a whole character movie

star again, because that was so much fun. But, other than

that, I can't tell you [laughs].

DR:

Thank you for your time.

With

thanks to Rachel Baglin and James Field at Substance

Eragon

is available to buy and rent on DVD from Twentieth

Century Fox Home Entertainment

from 16 April 2007.

Click

here

to buy the single DVD edition for £12.89 (RRP: £22.99)

Click

here

to buy the double DVD edition for £13.98 (RRP: £24.99)

Return

to...

|